Nick Johnston: ‘Child of Bliss’ Review

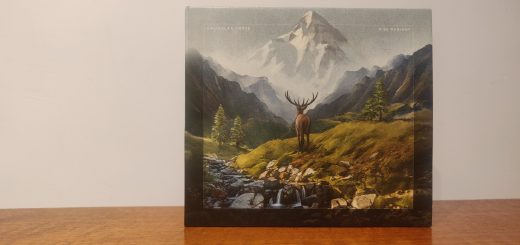

The album artwork for Child of Bliss

Pinpointing the soul of a guitarist can be a greatly difficult task. Canadian guitarist Nick Johnston wears his openly: through the years he’s managed to pinpoint a sense of purpose in his playing and refine it from record to record. Technically, much like contemporaries such as Guthrie Govan or Plini, there’s a good amount of shred, but here the focus is a generally mellower and more melodically inclined approach. Over the last decade, Johnston has released numerous solo albums (plus a brief spell in his acoustic-oriented and vocal-driven Archival project), with his seventh effort Child of Bliss primed and ready to dig into.

Seven albums deep as a fusion guitarist, your brand is generally in shred and vibes – how do you innovate, differentiate yourself, develop yourself? Johnston has adapted before, with changing line-ups and songwriting approaches over the years (prior solo effort Young Language even adding vocals into the mix). To my ear there is one clear consistency across his albums – “less is more.” Child of Bliss, however, dares to ask “what if more is more” – but not in the classic Ywngie Malmsteen sort of way. Though he surely could (and occasionally does, for a few seconds here and there), Johnston doesn’t turn into a shred-monster – instead opting for deeper soundscapes and more direct compositions, which come across as remarkably human and authentic.

This sound refinement is first actioned in the form of very prominent synthesizers and keyboards, played by Johnston himself – Moonflower having some beautifully delivered keys driving its introduction. The swirling synth layers popping up in album highlight Little Thorn land in a really satisfying way, and the central element of Through the Golden Forest being some very pretty and textural key/synth combinations really makes that track for me. Throughout the record, said synth layering brings with it a fuller and more immersive atmosphere that serves to differentiate somewhat from earlier material, but Child of Bliss is still very much a guitar record, with plenty of swoon-worthy leads and catchy melodies – Himawari being perhaps the most direct track in terms of its guitar focus.

The real boons of the album are the fantastic inclusion of strings courtesy of Eli Bishop, alongside Liam Mitro on sax and woodwinds. This more symphonic approach comes into play throughout, introduced well on title track Child of Bliss. Sax is generally used as a layering tool alongside the trademark “guitar you can sing to” approach, and its little moments where it pops into the foray – sufficiently demonstrated in Little Thorn – leave you wanting more.

There’s very little of a negative nature to say about this – coming in at a cool 37 minutes, the album also handily avoids the trap that a lot of instrumental albums run into, to my mind – being overlong and overstaying their welcome. My main point of criticism is that hearing the strings, sax and woodwinds and their use across the record, I would have liked more emphasis on them and more prominent opportunities for each to shine. While it makes a great deal of sense that as a record written around guitars, Child of Bliss is going to focus more on the aforemented instrument and show itself as less of a ‘band’ unit, there’s a lot of great talent here that could be showcased more and I’d hope that if these musicians accompanying Johnston carry on in a live line-up, that they’re given ample opportunity to jam it out onstage.

With Child of Bliss, Nick Johnston has crafted a deep and satisfying instrumental record, with plenty of space to showcase his melodic toolkit, and a little bit of space for some excellent talent alongside his own virtuoso status. Tracks such as Moonflower and Through the Golden Forest are a really strong showcase into what this refreshed energy brings, and a song on the caliber of Little Thorn is often hard to find. I would love to know how songs from this album translate live and if Johnston carries forward the expanded band lineup that really takes this record up a notch in his expansive canon of music.